The age of the budget airline has ushered in a new type of tourism. International travel, once the preserve of the rich, is now accessible to all, and we’ve taken that freedom and run with it, with air traffic booming from 1 billion passengers in 1990 to over 4 billion passengers in 2018. And that new age of international travel has unlocked a truly global society, where no corner of the world is inaccessible. We have more capacity for movement than ever before, and holidays on the other side of the world become not only normal but expected.

A self-fulfilling prophecy?

Communities that were once completely self-reliant are now dependent on foreign visitors for their income. But we have to ask ourselves: how much do they rely on tourism because we continue to go there?

The global reliance on tourism is a relatively recent thing. As our society has become more globalised, our structures have gradually shifted – in a not-so-distant past, nations were far more self-sufficient, including here in the UK. Food production, clothing, industry – outsourcing these overseas has meant that many of those once thriving, skilled communities are now dependent on tourism. Once that shift has happened, it is hard to retract.

Climate considerations

While flights to Thailand might support those communities on a short-term basis, does our air travel really benefit them?

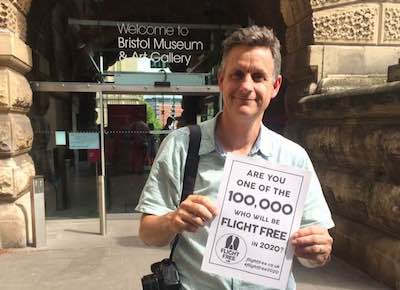

As our awareness of the climate crisis grows, it becomes ever more difficult to ignore the growing emissions from aviation, and to justify the holidays that cause them. Maja Rosén, founder of the Flygfritt campaign in Sweden, puts it quite succinctly: we want people to be able to travel, but if we don’t solve the climate crisis now, we are putting future travel at risk.

"We want people to be able to travel, but if we don’t solve the climate crisis now, we are putting future travel at risk."

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the island nation of the Maldives, famously at risk from sea-level rise. Advocates of 'sustainable tourism’ encourage us to visit for its eco credentials, not acknowledging the irony that by flying to reach it we are hastening its descent into the ocean. It’s the people who are least responsible for the climate crisis who will bear the brunt of it (and indeed, already are). These are the communities who are least equipped to deal with it, which is the brutal injustice of climate change.

What about the locals?

And we must not ignore over-tourism. The footfall of tourists in places such as Venice and Barcelona has a negative effect on the locals, from rising house prices, extra demand on services such as water and transport, and the conversion of local infrastructure into hotels and restaurants.

The beach in Thailand made famous by the film of the same name has now closed to visitors because of the impact of so many people flocking to see it. Ayres Rock has seen its last ascent, damaged from hundreds of thousands of feet tramping over its surface. Flying to Australia to see the rapidly-bleaching Great Barrier Reef will contribute to its demise. A new proposed airport at Machu Picchu would not only add to the already overwhelming numbers of visitors to the site, with the litter and erosion that brings, but would stretch the infrastructure of the town of Cusco to bursting.

"The footfall of tourists has a negative effect on the locals, from rising house prices, extra demand on services."

Nature is quick to recover when we stop visiting certain places – those beaches in Thailand, to which rare turtles are now returning, is testament to that. We would do well to remember that we share this planet with a great many creatures who are put at a disadvantage by our desire to see them.

Changing the way we travel

The good news is, not flying doesn’t mean not travelling. It just means travelling differently, and this shift is good for more than just the environment. Slow travel connects us with landscapes and cultures in a way that air travel doesn’t. It gives us a much more authentic travel experience. A work trip by train is less stressful and more productive than the equivalent journey by plane. Overland journeys can be sightseeing trips in themselves. As Eurostar puts it, ‘You see more when you don’t fly.”

"Slow travel connects us with landscapes and cultures in a way that air travel doesn’t."

We are so lucky with Europe – there is endless variety here on our doorstep. For breathtaking mountain vistas, look no further than Scotland. For soft white sand and blue seas there's the Mediterranean. Head to Spain for culture, food and great weather. And let's not forget our own tourism industry here in the UK – once flourishing, now suffering, and in desperate need of our attention. It’s so easy to overlook what is under our noses. Holidays, even adventures at home can be just as varied and exciting (and much cheaper) than anything else we might see in the world.

The real benefit for us and our planet

So while we might think we are helping far-off communities by visiting and spending our money, we should take a step back and consider the wider implications of our journeys.